Journey through the gastrointestinal tract

The miracle machine that is the gastrointestinal tract

Our gastrointestinal tract is a miracle of creation that has many more functions than “just” digesting food, which in itself is an extremely important and complex task. This is particularly noticeable when digestion does not work as it should. But did you know that your gut is of central importance for your immune system? Or that you have several 10,000 nerve cells directly in your gut? Or that you have a microbiome with around 100 trillion “good” bacteria in your gut? Is your interest piqued? More of this later! The intestine in particular is still far from being fully explored, as it is quite “remote” and cannot be “seen” in its entire length with an endoscope. This is because only about 30cm can be viewed from above during a gastroscopy and from below during a colonoscopy. The rest is shrouded in mysterious darkness. Let’s embark on a journey through the gastrointestinal tract.

Let the journey begin

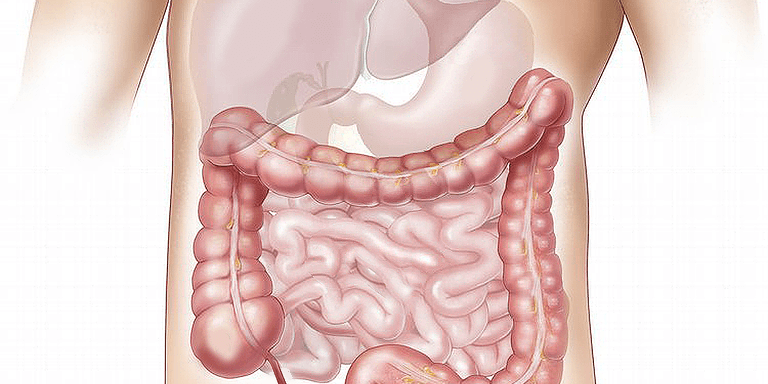

To summarise briefly, the journey of our food begins in the mouth, followed by the oesophagus, the stomach, the duodenum, the small intestine, the large intestine, the rectum and finally what remains of the food and what else the intestine has to get rid of leaves us at the anus. The distance between food intake and excretion is around eight metres and takes about three days! But what happens on the way? The food is broken down in the mouth and mixed with saliva. In the stomach, the food is then pre-digested into a chyme with the help of the extremely acidic gastric juice and the powerful movements of the stomach muscles (you can find out many more details about the stomach in our magazine under the topic “The stomach, an amazing organ!”). In the duodenum, the chyme from the stomach is deacidified and mixed with digestive juices, which are important for later absorption. Digestive enzymes that break down carbohydrates and proteins, bile salts for fat absorption and bases for neutralising stomach acid.

On the way in the small intestine

Now comes the mysterious section of the small intestine, which is the longest part of the gastrointestinal tract. Not only is it long, it also has a huge surface area in order to absorb as many nutrients as possible from the food. The amazing surface area of the small intestine is due to the multidimensional protrusion of the intestinal cells, so there is a lot of space in a very small area! The most important nutrients are absorbed in the small intestine: Sugar, amino acids, fat, vitamins and a large proportion of water. The intestinal layer is extremely thin, just as thin as a single cell. Important tasks await this thin layer of cells. They are exposed to a constant bombardment of toxins and pathogens. Once the food components have been broken down, they pass through this cell layer into the bloodstream and nourish your body.

Into the large intestine

Between the small and large intestine lies the appendix, a kind of stump, a dud. Everyone who has had to have it surgically removed due to an infection knows that you can live without it. The most common theory is that the appendix is a reservoir for “good” intestinal bacteria. As the name suggests, the large intestine is thicker (about as thick as a fist) than the small intestine, but “only” about one to two metres long. Firstly, water and salts are absorbed from the food in the large intestine. Everything that is still possible is removed from the chyme. The large intestine also harbours the so-called microbiome. It is an “organ” of its own, so to speak, consisting of around 100 trillion bacteria that are vital for our survival. Around 1500 types of bacteria can be counted, and the composition differs from person to person like a personal fingerprint! You carry around two kilograms of these extremely important bacteria!

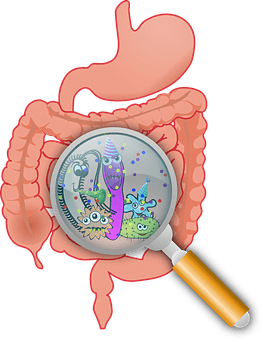

The microbiome

Microorganisms fulfil many important tasks! They ensure that certain nutrients can be properly utilised. They also produce vitamins and hormones. They protect the intestines from harmful substances and prevent pathogenic viruses, bacteria or fungi from settling in the intestinal mucosa and causing infections. They supply the immune cells, most of which are located in the intestine, with important information. Pathogens can thus be specifically combated. They also promote the development of the intestinal mucosa. However, all these tasks can only be accomplished if the microbiome is balanced, for which the microorganisms must be in a very specific ratio to each other. This explains the massive health problems that can occur if this ratio is out of balance! Damage to the intestinal tract causes metabolic and immune system disorders and has a negative impact on the quality of life of those affected.

The brain in the gut

The brain is in closer contact with no other organ than the gut. Surprisingly, however, around 90 per cent of information comes from the gut and not the other way round. Your gut contains a network of around 100 million nerves, the so-called abdominal brain. The cranial brain is responsible for thinking, while the abdominal brain independently takes care of digestion. Communication between the brain and gut is very active via the vagus nerve. The brain is considered to be the place where emotions arise, but recent findings have shown that gut bacteria also have a major influence here. Scientists have hypothesised that different strains of bacteria affect different areas of the brain and therefore emotions. All the more reason to endeavour to maintain a healthy gut flora!